- Home

- Anna Bruno

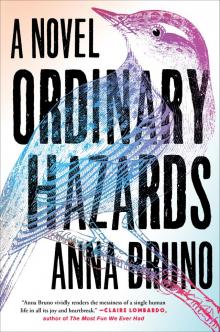

Ordinary Hazards

Ordinary Hazards Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Parker

We were victims of the tyranny of small decisions.

—Alfred E. Kahn, economist

5PM

THE FINAL FINAL IS the kind of bar that doesn’t exist in cities, a peculiarity of a small town that has seen better days. It is so called because it’s the last bar on the edge of town. The final stop after the final stop: The Final Final. By last call, there’s no place to go but home. The college kids head up the hill to the dorms and the working folks find their way to the outskirts, where they can afford to own property or rent for cheap.

The antique tin ceiling is the nicest thing in the bar, a sharp contrast to the vinyl floor, manufactured to look like wood, cracked and knotted. Vinyl isn’t fooling anybody, not even a bunch of drunks at the end of the night. But we all like the ceiling. The tin tiles belong in an East Village watering hole or a Tenderloin speakeasy. Polish and decay. I’m not sure how, but the black tin makes me want to stay so much longer and drink so much more—indeed, black magic.

I stare into my drink, and my peripheral vision catches movement around me, bodies adjusting on stools, sips of whiskey and long swigs of beer, wallets opening. Time is ours now—time for a first drink and a second, time to take the edge off. We’ve paid our daily dues, taxes have been levied, and we naively believe these hours belong to us and us alone—they are borrowed from no one—and they will remain in our possession until last call, and beyond last call, until we give them up to sleep, and to the morning, and then, once again, to the man, but only until five o’clock tomorrow, when we reclaim what is ours.

On the edge of my stool, arms resting on the thick, old wood bar top, gouged and scuffed by the drunks who came before, I feel this split in my being, like a schism. There are two of me: the woman I am and the woman I used to be. I wonder if these versions of myself can both exist, as if in two dimensions overlaid, or if they erase each other entirely: two extremes that average out to nothing more than middling. I close my eyes and the smell takes over—booze and dish soap—and I am her, the old me, and I can almost picture him walking through the door.

A gold band adorns my left ring finger. I haven’t taken it off. I’m playing with it, turning it around and around with my right thumb and index finger. I am more alone now than I was before because back then, before, I felt love, my body’s experience of this state: alive, my cheeks flush from the warmth of another, my lips red from a hard kiss, my muscles relaxed from endorphins; and after, I remember love, my mind’s recollection of this state: dead, a thing of past experience, beautiful but fleeting, a hummingbird that floats in place and then, in an instant, vanishes, never to return. The problem is not that I live in the past, the before; the problem is that I live in the present, the after.

* * *

LUCAS AND I MET five years ago, here at The Final Final. I’d been living upstate for less than a year at the time, adrift. I walked into this neighborhood dive to meet Samantha, my oldest friend, only to find she had sent a man in her place. He had messy, longish brown hair and a trimmed beard, and I remember he was wearing shorts because I thought it was an odd choice for a date, until I realized my presence was as much a surprise to him as his was to me. It was a blind-blind date, meaning we were blind to the notion of it—we hadn’t agreed to it. I received a text. It read, Emma meet Lucas. I’m sorry I can’t join you but I know you’ll have a smashing time! We caught each other looking at our phones. Lucas knew I was Emma, and I knew he was Lucas. He looked up and smiled, and we were both immediately grateful.

My first impression? I could have sworn he was Canadian. He was profoundly kind and unapologetically socialist—and by that I mean he didn’t believe money was the barometer of success—qualities that were alien to me and, at the same time, deeply attractive. In him, I’d found a Canadian-at-heart, who would never say eh or make me watch hockey. He was The One.

When Amelia delivered his third whiskey, Lucas raised his glass toward no one and said, “Lord, give me chastity but not just yet.” Surprise must have registered, ever so slightly, on my face. He looked down into his glass.

“St. Augustine,” I said, smiling, pleased with myself for catching the reference. He looked relieved. Lucas and I would eventually be able to read each other’s minds, but not yet. This was our first date, and there was a bit of first-date awkwardness—the good kind of awkwardness, the I-like-this-person-and-I-don’t-want-to-fuck-up kind of awkwardness.

Amelia filled my glass again too. We were on pace.

“Ahhh, I get it, Emma,” he said. He stared deep into my face, not my eyes but my whole face. “For a second I thought you were worried I drink too much, but you drink too much too.”

“Get what?”

“That look you just gave me,” he said.

“What look?”

“Promise me you’ll never start playing poker,” he said. “Because I think I could fall for you. And it would be a real tragedy if you lost all our money playing poker.”

I punched him on the arm. His bicep was firm. He wasn’t a big guy. His body was lean and taut, a runner’s body. He had masculine, hairy legs—strong calves and a great ass. I was attracted to him.

“Ouch.”

“You didn’t answer my question,” I said. “What look did I give you?”

“Surprise,” he said. “You weren’t expecting me to know St. Augustine.”

I’d been in The Final Final a couple of times before this blind-blind date, but I’d never noticed the flock wallpaper behind the bar, deep red with a gold-leaf trellis pattern, vintage and probably expensive when it was chosen. This backdrop suited Lucas, who seemed to me, even at this early meeting, to be from another world. The way he sipped his whiskey and talked about philosophers and pushed that flop of hair back on his head. It wasn’t that he belonged in another generation; quite the contrary, it was that he belonged in my generation but in a different dimension, where people weren’t brainwashed by social media. In Lucas’s dimension, minds were meant to wander, exploring various curiosities, and friends enjoyed long, uninterrupted conversations.

“Is that what I was thinking? You can read all that in one micro expression? Maybe you should quit the drywall business and become a fortune teller,” I said.

“More like a mentalist. Sure, I think I could if I wanted.” He pointed subtly, through his body, to a couple sitting at a high-top table. “First date. He’s trying too hard; she’s being polite. There will not be a second.”

“Well, it doesn’t take a genius—”

“So you’re telling me you weren’t surprised?”

“Not even a little bit,” I said. Then I thought about our friend Samantha and specifically why she chose to bring us together in exactly this way, the blind-blind date. If she’d done it differently, I would have asked her what he did for a living, and she’d have said something coy like, He works with his hands, and I would have pressed her and she would have told me but she would have qualified it with color commentary, He’s brilliant, and she would have been right but we would have already diminished him by the very need to qualify, and Lucas was a man who did not demand qualification.

As he walked me home, our arms brushed against each other a few times, and I felt a rush of teenage giddiness. I told him it was my thirtieth birthday.

“I thought I was meeting a friend,” I protested.

“Mission accomplished,” he said. He asked for my number but was so flustered he could not figure out how to get it into his phone. I took a pen out of my purse and wrote it on his hand. By the time I changed into my pajamas and washed my face, I knew he’d managed to get the number into the phone, where it belonged.

* * *

A FEW MORE LOCALS show up. Five o’clock is quitting time in our town. The clientele is mostly men—the regulars. Occasionally groups of girls come by for shots. They are from the university on the hill. This is their first stop as they make their way downtown.

Amelia has dark-brown hair and you can tell she’s pretty under all the makeup. She’s been working here since she was eighteen, twelve years and counting. According to New York State law, bartenders at places like these—places that don’t serve food except bar nuts and bags of potato chips—must be twenty-one, but back then everyone just looked the other way, even the cop who dipped in from time to time. Small-town liberty.

I’ve never seen Amelia dressed in anything but black hot pants—skin tight and short—and low-cut tops, even in the dead of winter. She dresses this way at the grocery store and the dog park too. I run into her sometimes.

She is the best bartender in town. She knows what you drink and when you’re ready for a refill. She pours whiskey generously. She makes a good martini. I think about all the secrets Amelia must be in on. She must know things about Lucas I can’t even imagine.

All the regulars drink their same thing all night. Cal drinks Bud Light from a bottle. As he drinks his piss beer, he talks about his “bunker,” which is his basement, filled with guns and ammo, rice, water, and canned goods. He never takes off his maroon sport coat, even when the bar gets hot, because it conceals a handgun in a holster, which rests about midway up his left side, between his belt and his armpit, so he can reach in quickly with his right hand. There are two Peters. Fancy Pete drinks white wine served in individual portioned bottles, like you see on airplanes, which Amelia unscrews for him, and he pours into a wineglass. Short Pete drinks gin and tonics. Fancy Pete makes his own pants and furniture and Frank Lloyd Wright–type lamps. Short Pete is tiny, smaller than a petite woman. No one calls him Tiny Pete, though, only Short Pete. I drink bourbon, almost always Maker’s Mark, because it’s as close to perfect as I’ve found.

Cal is talking about Jimmy, Lucas’s best friend. Lucas and Jimmy grew up together, played on the same soccer teams, drank twenty-four packs of Busch Light in the cemetery after dark. Jimmy is a line cook at the greasy spoon up the street. He’s thirty-five but he looks older.

“He fancies himself a chef,” Cal says.

I wonder if Lucas talks to Jimmy as much now as he always did. There was a period when he called him about three times a day. Jimmy: the human encyclopedia. Whenever Lucas had a question about history or current events, he called him. It was pretty obvious he used these requests for information as excuses to call his buddy. Perhaps it was a male thing, I thought—needing an excuse. Later, when I knew Lucas inside and out, I came to understand that he called Jimmy for Jimmy’s sake—that it was Jimmy who needed to be needed, and that Jimmy loved rattling off information as much as Lucas enjoyed absorbing it. The truth is probably somewhere in between—the two men needed each other, albeit in different ways.

“Yesterday he was in here talking about salmon with pickled radishes and foamy tapioca balls,” Fancy Pete says.

“Foamy tapioca? No self-respecting man would eat that,” Cal says.

“Lucas would.” Fancy Pete chuckles.

Foam is a big deal in New York City right now. I don’t say that, though, because I don’t want to remind these guys I’m from Wilton, even though it drips from me here.

“I got breakfast at Jimmy’s place this morning, and I tell you what—there wasn’t one tapioca ball in the place. Every last one of us ate eggs and bacon with a side of black coffee,” Cal says.

All the locals call the diner Jimmy’s place. That’s not its real name and Jimmy doesn’t own it, but he’s always there so it’s his place. There are days, when his eyes are especially puffy or when he tips up his hat to scratch his scalp, hair greasy and unkempt, that I’m sure he’s slept there. When Jimmy leaves the bar, he goes back to the diner and cleans up the kitchen for an hour or so, rectifying details the closer—some college kid, drunk or stoned—missed. Then he preps for tomorrow, which comes so fast. Jimmy’s place opens at six a.m. So, for Jimmy, a night’s rest is often a nap on the two-seater couch in the back office. I picture his enormous frame splayed on top of it, legs bent over the armrest, going numb. My feelings about the way he lives are ambivalent—pity for the discomfort of his situation but also a strange, misplaced envy because he has found a way to avoid those hideous dreams that leave a person worse off for having slept.

“Man,” Cal says, “this town is full of tapioca balls these days. Jimmy can serve foamy balls to tapioca balls. Might get stuck in their beards, though.”

I can’t help myself. “The foam and the tapioca are two different things.”

He moves his head from side to side and snaps his fingers. Cal’s hands are thick and sturdy, and one of his fingernails is black: a workman’s hands. Under his maroon sport coat, he’s wearing an old golf shirt with the embroidered logo of his general contractor business. He must have a few of these in rotation because he wears them just about every day until the temperature drops and then he switches to old flannels. His wrist is adorned with an expensive watch. Large and gaudy, the watch draws attention both because of what it is and the man who wears it. It suits him, and at the same time, it doesn’t.

“I’m just saying: tapioca is one thing—your mom probably makes pudding with it—and foam is another thing,” I say.

“Now you’re talkin’ about his mom?” Fancy Pete says. “Hey, Cal, tell your mom I’ll eat her tapioca any day.” He rocks his body back and forth like he’s riding a horse and pretends to slap it on the ass.

“Shut the fuck up,” Cal says.

Cal is in his late thirties. He was a few years ahead of Lucas and Jimmy in school and didn’t play soccer, so he ran in different circles growing up. He met a girl in high school, Evie. They got married at twenty-two and eventually had a daughter. They named her Summer because she was born in July. I don’t know all the details, but when Summer was just a toddler, Evie hit the road, late to follow some unapologetic jam band that had peaked in the late nineties, Widespread Panic or Phish.

I never once heard Cal complain, not even when they divorced. He loves Summer too much, sees her as a gift from the ex-wife or God or both, and everything he does, in and outside of the law, is because of her and for her.

Cal is a tradesman at heart but also a hustler. Straight out of high school, he got a job tying rebar for various projects, most notably for an undulating concrete wall that cuts through the park in the middle of town. He is proud of this job and talks about it to this day. He refers to it as “my wall.”

He tied rebar for minimum wage for a year or two, until one of the old-timers from the bar took him under his wing. This all went down long before I set foot in The Final Final, but as the story goes, Cal needed work so he asked the old-timer if he had anything. The old-timer saw something in Cal, and without children, he had no one else to whom he might pass his business. So he sold Cal everything—his clients and all the equipment—for ten grand, which Cal borrowed from his dad. Then the old man worked for Cal, watched him grow the business.

Most people think of inheritance as money handed down, but not Cal. For him, inheritance is earned like everything else.

* * *

WHEN LUCAS AND I had just started seeing each other, Cal told me he didn’t understand him. “You know how much money I contracted out to Murphy’s Drywall last year?”

Apparently, Cal was pushing several jobs a year to Murphy’s Drywall, big jobs,

making up maybe a quarter of their business. According to Cal, Lucas was never the one who submitted the estimate—each time the bid came from Lucas’s dad. Cal saw Murphy’s Drywall as a cash cow. He saw it as Lucas’s birthright. And for the life of him he couldn’t figure out why Lucas wasn’t taking on more responsibility there, why he acted like paid labor.

“Lucas is a turnip,” Cal said. I remember this specifically. It struck me as an odd thing to come out of Cal’s mouth, not because he was talking about Lucas, but because it reminded me of something my father would say. He loved to call women, whom he found ineffectual, pumpkins. And though he had never called Lucas a turnip, I had no doubt he would, given an appropriately impudent mood and a couple of whiskeys.

There was something quaint about comparing people to fruits and vegetables. Lucas would have found it funny.

I didn’t agree with Cal but I let it pass.

For Cal, more so than any of the other regulars, I feel a certain loyalty—not friendship, but not far off. He gave Lucas sound advice early in our relationship, advice born out of clear-eyed devotion to his daughter, and maybe also to his ex, even though she’d left him. Without his advice, I’m not sure Lucas and I would have worked through an early hurdle.

When we first met, Lucas was in a relationship with someone else: Angela.

Lucas and Angela lived next door to each other growing up. Angela’s mother helped the Murphys with their taxes, and later, after she graduated with an accounting degree from the U., Angela took over the role. Lucas was sure she’d never traveled outside of Upstate New York, where most of her family lived, never even to the city.

As kids, they did kid stuff together. Back in the early nineties, Lucas apparently called for a pizza and then went outside where she was playing and typed in the order as a note in his TI-81 calculator, telling her Pizza Hut had this amazing new system. When the delivery guy showed up, it blew her mind. Later, he let her in on the joke.

Ordinary Hazards

Ordinary Hazards